This post is the third and final entry in my recent series exploring who might have breakfasted with John Wilkes Booth on the morning of Lincoln’s assassination. The first installment explored the identity of Carrie Bean, a young socialite that journalist George Alfred Townsend claimed shared breakfast with Booth on April 14, 1865. The second post discussed the theory that Booth was joined that morning by his own secret fiancee, Lucy Hale. For this third post, we’re going to consider a third woman to whom an intriguing connection to Booth’s breakfast has been made. Her name is Cynthia Ann Brooks. According to articles from her granddaughter, John Wilkes Booth gave Cynthia Brooks his picture at breakfast on the morning of Lincoln’s assassination.

First, the verifiable facts I have been able to glean about the family in question. Cynthia Ann was the daughter of Joseph and Elizabeth Allen. She was born in about 1812 in Maine. Her family claimed kinship to the Revolutionary War patriot Ethan Allen, who, along with Benedict Arnold, captured Fort Ticonderoga from the British in May of 1755 without firing a shot. As a young child, Cynthia’s family moved to Hamilton, Ohio, a town just north of Cincinnati. At around the age of 20, Cynthia married Eri V. Brooks, a police officer and justice of the peace in Hamilton. The couple had at least five children. In 1850, Eri Brooks died, so Cynthia Brooks and her children moved in with her brother, William Allen.

In 1857, Cynthia’s eldest daughter, Clara Belle Brooks, married a man named Richard Hall. The young couple moved to Superior, Wisconsin, where Richard and Clara’s brother, Eri Brooks, Jr., set up a law firm. The firm eventually moved to Houghton in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. While Eri became a justice of the peace in the area, Richard and Clara were unhappy with life in the isolated far north. The couple moved to Indianapolis, which was Richard’s hometown. There, in 1859, the Halls gave birth to a daughter, Clara “Carrie” Hall. In 1860, Richard accepted a position as a clerk in the Census Bureau in D.C. As a result, he moved his family to the nation’s capital. Young Carrie Hall would grow up in the bustling streets of Washington.

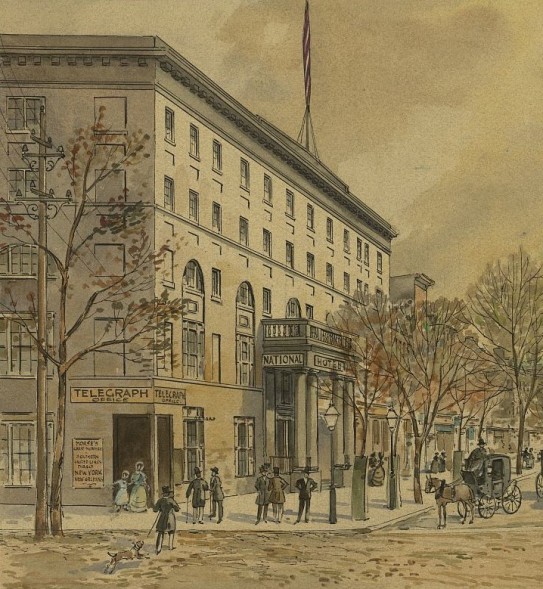

In 1861, Richard Hall was transferred over to the Pension Bureau. He was employed there until 1864, when he resigned from his government position in order to become a real estate broker. Richard was involved in political matters and took part in events at the city’s Union League. He was a strong supporter of Abraham Lincoln and spoke passionately in favor of the President at the Union League in the lead-up to the 1864 election. During their time in D.C., the Hall family lived in a variety of residences. By 1865, however, the Washington city directory shows the Halls lodging at everyone’s favorite locale: the National Hotel.

Between 1865 and 1867, Richard served a stint as the D.C. Recorder of Deeds. Near the middle of 1867, Richard left the government once again in order to return to his life as a real estate dealer. Not long after starting up his real estate business again, Richard was called for jury duty in the district. On June 13, Richard reported to the courthouse, and, like every American, he tried hard to get out of jury duty. Richard informed the court that, being a real estate agent, “the interests of other persons would suffer, perhaps, a great deal more than my own” if he were chosen to serve on a jury. The court was unmoved by Mr. Hall’s claims that his business could not wait for him to complete jury service. The court responded that his business excuse “would let off nine out of every ten of the jury” if they accepted it. He was ordered to stay and became one of the prospective jurors for an upcoming trial. Later that day, Richard Hall was interviewed again by the court, with the addition of lawyers from the prosecution and defense. This process, known as voir dire, allows the lawyers to judge prospective jurors’ knowledge of the case and their ability to be impartial based on the evidence. The case that Richard Hall was a prospective juror for was that of the escaped Lincoln conspirator, John Surratt, Jr., who had recently been captured abroad and returned to the United States.

Richard Hall knew that John Surratt’s trial would be a lengthy one, and he had no desire to sit on the jury day in and day out. Thus, when asked by the court if he had already “formed or expressed an opinion in relation to the guilt or innocence” of John Surratt, Richard replied with “Yes, sir; I have.” Pressed further whether his opinion on the case would bias or prejudice him in listening to the evidence and rendering a verdict, Richard Hall stated, “There are some facts in connection with the case that I think would very strongly prejudice my mind.” When asked a similar question by the prosecution, Mr. Hall reiterated that “I would, if compelled to sit as a juror, listen to the facts and to the evidence, but I have no hesitancy in saying that my judgment would be greatly influenced by circumstances.” Richard Hall was trying his hardest to get out of jury duty for John Surratt’s trial, yet his responses didn’t relieve him. The defense made no objection to his selection as a juror, perhaps seeing his honesty as the best they could hope for from a jury pool where everyone had an opinion about John Surratt. Richard Hall did not come across as biased enough to be dismissed.

Jury selection for John Surratt’s trial took much longer than anticipated. June 15 had been set as the cutoff for when the jury had to be impaneled, or else Surratt’s trial could not begin until the next court term. As a result, the prosecution was scrambling to narrow down the possible jurors to the 12 they needed. This worked to Richard Hall’s advantage. On June 15, he was called, once again, to be interviewed for voir dire. However, he failed to respond to his name, with it later being reported that he was “sick”. His absence, combined with the requirement that the jury be selected on this date, meant that Mr. Hall successfully avoided becoming a member of John Surratt’s jury of his peers.

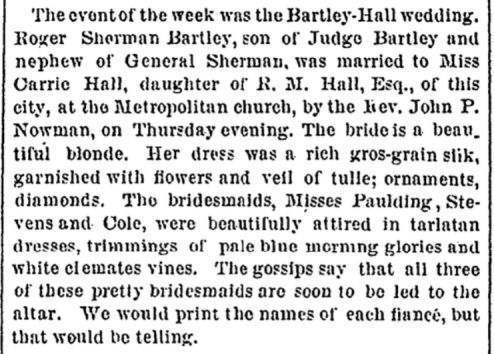

In the 1870 census, Richard, Clara, and Carrie Hall are all recorded as living at the National Hotel. Seven years later, 18-year-old Carrie was engaged to be married. Her beau was a man named Roger Sherman Bartley, and he was the nephew of General William Tecumseh Sherman. The couple’s wedding on December 27, 1877, was a celebrated event that made the D.C. papers.

In addition to the famous general, one of Roger Sherman Bartley’s other uncles was John Sherman, who had a long career in politics. From 1877- 1881, John Sherman was the Secretary of the Treasury, and through this connection, Roger Bartley was able to find employment. In 1880, Roger and Carrie moved to Denver, Colorado, where Roger was assigned as an assistant clerk in the small branch of the U.S. Mint located there. The branch tested and melted down gold into bullion for shipment to other branches. Roger and Carrie made their home in Colorado and had four children together.

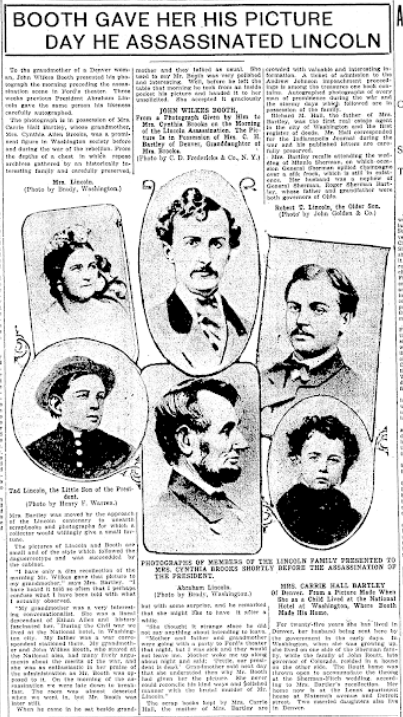

In the early 1900s, at least three articles were published in the Denver Post newspaper featuring interviews with Carrie Hall Bartley. The first occurred on October 7, 1901, and was titled “The Souvenir of an Assassin“. This was followed by the article “Booth Gave Her His Picture Day He Assassinated Lincoln” on February 8, 1909. And finally, “Autograph Lincoln Pictures Treasured by Mrs. Welker” was published on February 12, 1917. Carrie divorced Roger Bartley in 1910 and, in 1912, married a Christian Science practitioner named Lloyd William Welker. This is the reason her name has changed in this last article.

In each of these articles, Carrie Hall recalls her time as a young girl living at the National Hotel in 1865. The middle article actually contains an image of Carrie Hall taken when she was a young girl in Washington:

Carrie recounts that her grandmother, Cynthia Brooks, resided in D.C. along with her and her parents during the Civil War. The 1865 city directory and 1870 census confirms the Halls resided at times at the National Hotel. As our previous entries have demonstrated, the National Hotel was often a convergence point for the who’s who of D.C. As a result, Mrs. Brooks had the opportunity to rub elbows with the high society of Washington. In 1864 and 1865, this came to include the famous actor John Wilkes Booth. Carrie stated that:

“My grandmother was a very interesting conversationalist…[she] and John Wilkes Booth, who stayed at the National also, had many lively arguments about the merits of the war, and she was as enthusiastic in her praise of the administration as Mr. Booth was opposed to it… She used to say Mr. Booth was very polished and interesting.”

The three articles also describe Cynthia Brooks’ supposed run-in with John Wilkes Booth at breakfast on the morning of Lincoln’s assassination. Each is a bit different, so we’ll take them one at a time.

“The Souvenir of an Assassin” from 1901 tells Carrie Hall’s story, but she is not quoted in the article. It narrates that Carrie and her grandmother were among the last people at breakfast on the morning of April 14, 1865. This was due to young Carrie feeling ill that morning. John Wilkes Booth was the only other person at the breakfast table with them at this late hour. Apparently, Mrs. Brooks shared with Mr. Booth that the family had plans to attend Ford’s Theatre that night. Before departing from the table, Booth, “gave a penny” to Carrie, “and his picture to her grandmother – both child and grandmother comparative strangers to him – as souvenirs. The penny was spent for candy, but the picture was preserved with a pitiful likeness of the martyred president to offset it.”

There isn’t much more detail in this first article about the interaction, and it portrays Mrs. Brooks and Booth as being relative strangers. In addition, the article implies the image was given to Mrs. Brooks because Booth knew “what part he was to play in the performance” at Ford’s Theatre later that night. However, while assassination was certainly on Booth’s mind, he did not know at breakfast that the Lincolns had accepted the invitation to attend Ford’s Theatre. That knowledge was only conveyed to him when he visited Ford’s after breakfast to pick up his mail.

The 1909 article “Booth Gave Her His Picture Day He Assassinated Lincoln” is the most detailed of the three and includes quotes from Carrie Hall. It is from this article that we learn that Cynthia Brooks was a “prominent figure in Washington society before and during the war of the rebellion” and where the prior quotes about her conversations with Booth come from. Carrie starts her narration with an acknowledgment of the imperfect nature of memory:

“‘I have only a dim recollection of the morning Mr. Wilkes gave that picture to my grandmother,’ says Mrs. Bartley. ‘I have heard it told so often that I perhaps confuse what I have been told with what I actually observed.”

Carrie then recounts that she and her grandmother were late to breakfast on April 14th but that “Mr. Booth was later still.” When he came into the breakfast room, Booth sat down next to Mrs. Brooks, and they talked as usual.

“Well, before he left the table that morning he took from an inside pocket his picture and handed it to her unsolicited. She accepted it graciously but with some surprise, and he remarked that she might like to have it after a while.

She thought it strange since he did not say anything about intending to leave.”

Carrie recalled that her parents and grandmother were planning on attending Ford’s Theatre that night, but they didn’t go because the young girl was sick. They heard the news like everyone else in the city, and Clara Hall woke Carrie up to tell her of Lincoln’s assassination.

“Grandmother said the next day that she understood then why Mr. Booth had given her his picture. She never could reconcile his kind ways and polished manner with the brutal murder of Mr. Lincoln.”

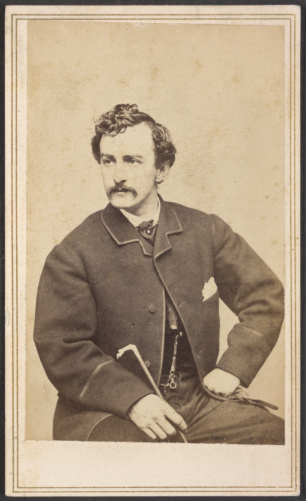

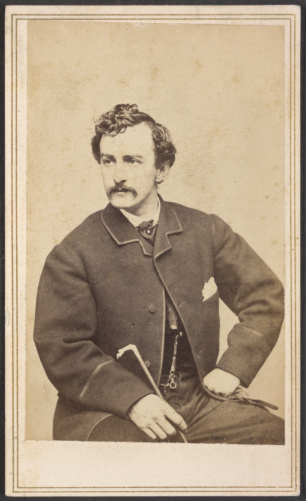

While the 1901 article reproduced the image of Booth that was given to Cynthia Brooks, the process of digitizing it made it difficult to see. From this 1909 article, we can more clearly see that Mrs. Brooks was gifted with a copy of this photograph of Booth:

This article was decorated not only with the image of Lincoln mentioned in the 1901 article but with other images of the Lincoln family as well. According to a throwaway caption, these were “photographs of members of the Lincoln family presented to Mrs. Cynthia Brooks shortly before the assassination of the President.” We’ll address these images again in a little bit.

The final article that I have been able to find comes from 1917, just a year before Carrie’s death. On the anniversary of Lincoln’s birth, the now-named Carrie Welker showed off her collection of images to the Denver Post once again. Carrie is not quoted in this piece, and her story is told by the reporter who interviewed her:

“On the morning of the day Lincoln was assassinated, Mrs. Brooks, who was living at the then famous old National hotel on Pennsylvania avenue, was late for breakfast. As the main dining room was closed, she ate in a small private dining room, just off the main parlor. While breakfasting, J. Wilkes Booth, whom she knew well, entered the parlor, and, seeing her in the next room, entered and sat down with her at the table to chat a few minutes. Before leaving, he said: ‘Mrs. Brooks, may I present you with my photograph?’ And he took a picture from his pocket and gave it to her.”

There is no mention of Carrie having been present with her grandmother at breakfast that morning. The article does recount the story that the Halls had tickets to attend Ford’s Theatre that night but did not go on account of Carrie’s illness.

While there is little information in relation to the story of Booth presenting his image to Mrs. Brooks, this article does add a brand new story revolving around the images of the Lincoln family in Carrie’s collection. According to this 1917 article, Richard Hall was “Lincoln’s friend” who was, “very closely associated with the president.” It continues:

“Shortly before Lincoln was assassinated he had some new photographs taken of himself and the members of his family. He considered these particularly good. Almost at the same hour that Booth was giving his picture to Mrs. Brooks[,] Lincoln presented a set of the new photographs of himself and family to Mr. Hall. Included in the set were pictures of the president, Mrs. Lincoln, Thaddeus [sic] Lincoln and Robert Lincoln.”

This entire paragraph is almost assuredly untrue. Richard Hall was a Lincoln supporter, and perhaps he had been fortunate enough to meet the President at a social function once or twice, but there is nothing to support the idea that the two men were friends. In addition, the images supposedly given to Mr. Hall by the President were not “recent” images of the Lincolns, as stated. The photograph of Mrs. Lincoln was taken in January of 1862, while the portrait of Lincoln in profile dates to February of 1864.

It’s interesting how the images of the Lincoln family increased in importance over the years. In the 1901 article, the portrait of Lincoln was described as “pitiful” and merely an image kept adjacent to the image gifted to Mrs. Brooks by John Wilkes Booth. In the 1909 article, a caption merely states the Lincoln family images were “presented” to Mrs. Brooks, with no statement of by whom. Then, in this 1917 article, the images of the Lincolns are the most important pictures, gifted to Richard Hall by Abraham Lincoln personally. In addition, the article’s title called them “Autographed Lincoln Pictures,” even though there is nothing in the article that suggests any of the images are autographed.

While there’s no reason to believe the part of the 1917 article that deals with the Lincoln images, what about the overall claim that Cythnia Ann Brooks spoke with John Wilkes Booth at breakfast on the morning of the assassination and was given a photograph by the actor? While there were some small changes across these three articles, this part of the story stayed largely consistent over the 16 years.

John Wilkes Booth was known to present his photographs to friends and acquaintances. In fact, on February 9, 1865, Booth wrote to his friend Orlando Tompkins in Boston, asking the man to visit the photography studio of Silsbee, Case and Company in that city for him. He wanted the proprietor, John G. Case, to “send me without a moments delay one dozen of my card photghs… as there are several parties whom I would like to give one.” As much as I would love for Cynthia Brooks to have been the recipient of one of these images, Booth specifically requested not the photograph in Carrie Hall’s collection, but this one of him seated with a black cravat and cane:

After the assassination of Lincoln, this same image would be used on the wanted posters for Booth and his conspirators.

Unfortunately, there is no way to verify the story of Cynthia Brooks and her Booth photograph. Richard, Clara, and Carrie Hall were living at the National Hotel in 1865. However, try as I might, I have not been able to verify that Cynthia Brooks lived at the National or was even in Washington at the time of the assassination. It’s very possible that she did visit D.C. during the war years to see her daughter and granddaughter, but I don’t have any documentation to prove it. In truth, I have been unable to find records of Cynthia Brooks after the 1860 census. In 1871, Clara Hall included her mother’s name on an application for an account at the Freedman’s Bank, insinuating that Mrs. Brooks was still alive at that time, but I have not been able to find her anywhere.

The account of John Wilkes Booth presenting his image to Cynthia Brooks at breakfast on April 14, 1865, is an example of family lore. It’s a story that was passed down to Carrie Hall, who was too young to truly remember the events herself. It could be a real event, or perhaps it was a misremembered story of having seen Booth while the Halls were living at the National Hotel that merely evolved over time.

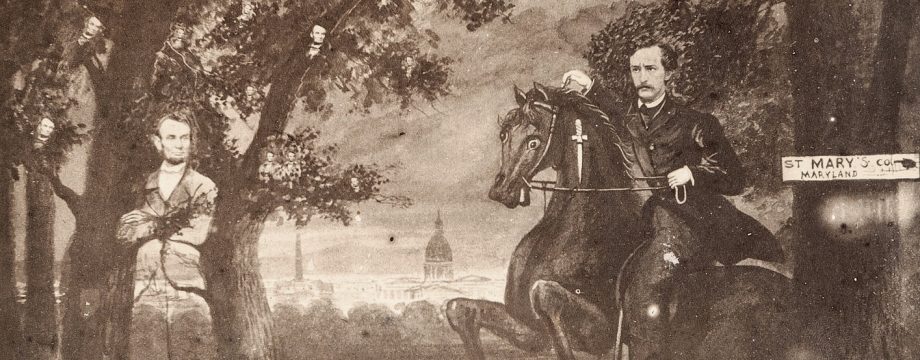

This series on John Wilkes Booth’s breakfast ends with far more questions than answers. Did he share a silent, but polite meal with Cara Bean? Did Lucy Hale make an appearance and interact with her fiancee for perhaps the last time? Or did Booth dine alongside Cynthia Ann Brooks and her granddaughter before presenting them both with small tokens of his esteem? In truth, we’ll never know the exact circumstances of this meal. All we do know for sure is that this was the last breakfast John Wilkes Booth ever ate as an actor. The next morning, the nation gathered at their own breakfast tables and read the shocking news of how John Wilkes Booth had now become an assassin.

Extra content:

While researching the family of Cynthia Brooks, I came across several interesting things. I already shared how her son-in-law, Richard Hall, was almost a jury member on John Surratt’s trial in 1867. This connected the family to Lincoln’s assassination in two different ways. However, the family actually has a connection to more than Lincoln’s assassination.

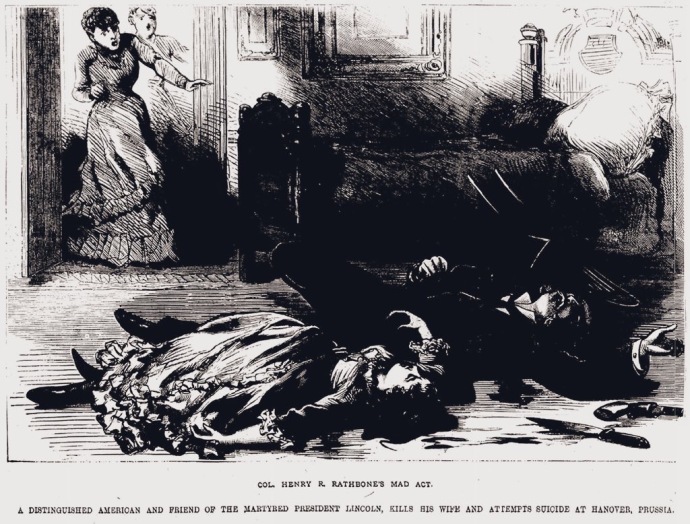

According to the article from 1901, Cynthia’s daughter Clara Hall attended the trial of Charles Guiteau in 1881. While there, Mrs. Hall shared a similar interaction with the assassin of President Garfield as her mother did with Lincoln’s killer years before:

“Mrs. Hall was attending the Guiteau trial and was seated facing the murderer. Feeling that he was the center of international interest, and that any little attention from him would be of great moment, Guiteau wrote his name with the customary flourish and handed it over to the surprised lady. Guiteau’s personal vanity stood out strongly to the very moment of execution.”

The article reproduced the autograph Charles Guiteau handed to Clara Hall, including Mrs. Hall’s explanatory notes about it:

The Brooks/Hall women had connections to unstable men beyond their interactions with Presidential assassins. In 1880, Clara divorced Richard Hall after he abandoned her and left D.C. for Tucson, Arizona, attempting to make a fortune as a miner. During a visit back east a year later, Richard Hall was said to have suffered a bout of paralysis in which he “lost his mind”. Richard was committed to an asylum in Indiana and died there in 1882 at the age of 49.

In 1910, Carrie Hall Bartley filed for divorce against her husband, Roger Sherman Bartley, on account of “another woman”:

“Mrs. Bartley testified that her husband packed up his belongings in October, 1908, when they were living in Fort Collins, and went to a hotel, instructing her to vacate the house in a short time, as he proposed to be responsible for her shelter and support no longer.”

After 32 years of marriage, Carrie requested $25 a month in alimony from Roger due to his desertion and entanglements with another woman. The judge ordered that Roger pay Carrie $50 a month instead. After the divorce, Roger Sherman Bartley eventually went on to marry a woman 31 years his junior named Edith Stoneback.

However, Carrie was actually the first of the two to remarry. Her second husband was Lloyd William Welker, a musician turned Christian Science practitioner. Their marriage was a seemingly happy and affluent enough one, as an article from 1917 noted that Mr. and Mrs. L. Will Welker were, “driving one of the handsomest new inclosed roadsters in town.”

Carrie Welker was a Christian Science practitioner like her husband. These are effectively faith healers who attempt to heal illness and pain through prayer. Carrie and L. Will operated out of an office where they met with and prayed with patients. According to Carrie’s obituary, “she was to all appearances enjoying perfect health” while tending to patients on Friday. Then, while at home on Saturday, June 15, 1918, Carrie Welker, “laid down for a few moment’s rest and while sleeping passed to the great beyond.” She was 58 years old.

In 1920, L. Will Welker remarried a singer by the name of Elsa Weffing. Elsa Welker died in 1930. In 1932, L. Will married a fellow Christian Science practitioner named Nelle Carr. Nelle Welker died in 1936. In December of 1937, L. Will married a woman named Agnes Durham who died two months later. Now, when I was relating this history to my true crime podcast-obsessed wife, Jen, she immediately told me that L. Will Welker seemed like a serial killer slowly knocking off his wives. I’ll admit that the numbers don’t look great for L. Will Welker. The fact that Carrie’s obituary stated she was in perfect health before she just fell asleep and died looks mighty suspicious as well. Additionally, there is an account of a man named Claude Poston who disappeared on December 3, 1915. The last place Poston had been seen was at L. Will’s Christian Science practitioner office where he had come for a session. His body was found seventeen days later, frozen solid in a ravine. All of this seems to support Jen’s hunch that L. Will Welker just might have been a serial killer.

But, at the same time, the view of Christian Scientists was that all healing was possible through prayer, so many did not seek out traditional medical help for their illnesses. This led to much higher fatality rates among Christian Scientists. L. Will Welker’s other wives may have died from a lack of medical treatment, believing they could solely pray their way to healing. Elsa Welker was noted to have been in ill health for a year before she died, even though she was only 45. Claude Poston, the man who ended up frozen in a ravine, had been praying with Welker in an attempt to help with his bouts of amnesia. His wife believed that Claude got confused after leaving Welker’s office, stumbled out into the woods, and ended up dying from exposure in the ravine he was found in. So perhaps there is nothing nefarious about the many deaths surrounding Lloyd William Welker. He lived a long life, himself, dying in California in 1959. (Jen still posits he might have been a serial killer, though).

There was one final little nugget I was able to uncover that still needs more investigation. While trying to determine what happened to Cynthia Brooks after her appearance in the 1860 census, I tried tracking down her other children aside from Clara Hall, hoping she might have moved in with one of them. I didn’t have much luck, but I did stumble across an article that mentioned Cynthia’s eldest son, Eri V. Brooks, Jr. As I wrote before, Eri had formed a law firm with his brother-in-law, Richard Hall, in Wisconsin and then Michigan before Richard and Clara moved away. When that happened, Eri Brooks, Jr. stayed in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan and became a judge there. In 1910, a small article appeared in different newspapers stating that a discovery had been made at the Eagle River Court House among the effects of Judge Brooks, who had died several years before. The discovery was a document containing a case from 1857. The case concerned the disposition of a canal boat called the White Cloud. The boat had been ordered seized due to a $40 debt owed by the owners of the boat to a 14-year-old boy. The fourteen-year-old who was owed the money and had brought the suit was a young William McKinley.

I’m not an expert on President McKinley, but I am curious about this suit and whether there is any truth to this article. I’ve reached out to the experts at the McKinley Presidential Library, and we’ll see if they can find anything about this case. If I learn anything about it, I’ll post a comment below at a later date. Still, if Eri Brooks did have this document in his papers, then the Brooks family has a small connection to yet a third assassinated U.S. President.

Recent Comments